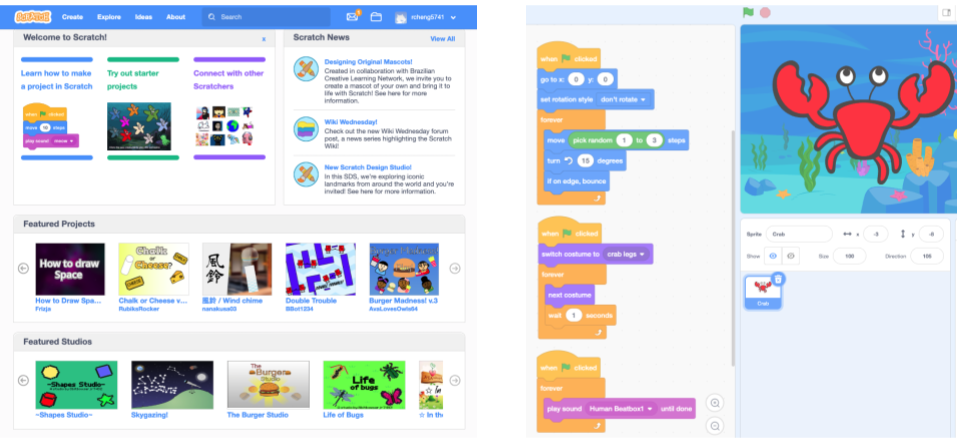

Thousands of widely used online communities are designed to promote learning. Although some rely on formal educational approaches like lesson plans, curriculum, and tests, many of the most successful learning communities online are structured as what scholars call a community of practice (CoP). In CoPs, members mentor and apprentice with each other (both formally and informally) while working toward a common interest or goal. For example, the Scratch online community is a CoP where millions of young people share and collaborate on programming projects.

Despite an enormous amount of attention paid to online CoPs, there is still a lot of disagreement about the best ways to promote learning in them. One source of disagreement stems from the fact that participants in CoPs are learning a number of different kinds of things and designers are often trying to support many types of learning at once. In a new paper that I’ve published—and that I will be presenting at CSCW this week—I conduct quantitative analyses on data from Scratch to show that there is a complex set of learning pathways at play in CoPs like Scratch. Types of participation that are associated with some important kinds of learning are often unrelated to, or even negatively associated with, other important types of learning outcomes.

So what exactly are people learning in CoPs? We dug into the CoP literature and identified three major types of learning outcomes:

- Learning about the domain, which refers to learning knowledge and skills for the core tasks necessary for achieving the explicit goal in the community. In Scratch, this is learning to code.

- Learning about the community, which means the development of identity as a community member, forming relationships, affinities, and a sense of belonging. In Scratch, this involves learning to interact with others users and developing an identity as a community member.

- Learning about the practice, which means adopting community specific values, such as the style of contribution that will be accepted and appreciated by its members. In Scratch, this means becoming a valued and respected contributor to the community.

So what types of participation might contribute to learning in a CoP? We identified several different types of newcomers’ participation that may support learning:

- Contribution to core tasks which involves direct work towards the community’s explicit goal. In Scratch, this often involves making original programming projects.

- Engagement with practice proxies which involves observing and participating in others’ work practices. In Scratch, this might mean remixing others’ projects by making changes and building on existing code.

- Feedback exchange with community members about their contributions. In Scratch, this often involves writing comments on others’ projects.

- Social bonding with community members. In Scratch, this can involve “friending” others, which allows a user to follow others’ projects and updates.

We conducted a quantitative analysis on how the different types of newcomer participation contribute to the different learning outcomes. In other words, we tested for the presence/absence and the direction of the relationships (shown as the orange arrows) between each of the learning outcomes on the top of the figure and each of the types of newcomer participation on the bottom. To conduct these tests, we used data from Scratch to construct a user level dataset with proxy measures for each type of learning and type of newcomer participation as well as a series of important control variables. All the technical details about the measures and models are in the paper.

Overall, what we found was a series of complex trade-offs that suggest the kinds of things that support one type of learning frequently do not support others. For example, we found that contribution to core tasks as a newcomer is positively associated with learning about the domain in the long term, but negatively associated with learning about the community and its practices. We found that engagement with practice proxies as a newcomer is negatively associated with long-term learning about the domain and the community. Engaging in feedback exchange and social bonding as a newcomer, on the other hand, are positively associated with learning about the community and its practice.

Our findings indicate that there are no easy solutions: different types of newcomer participation provide varying support for different learning outcomes. What is productive for some types of learning outcomes can be unhelpful for others, and vice versa. For example, although social features like feedback mechanisms and systems for creating social bonds may not be a primary focus of many learning systems, they could be implemented to help users develop a sense of belonging in the community and learn about community specific values. At the same time, while contributing to core tasks may help with domain learning, direct contribution may often be too difficult and might discourage newcomers from staying in the community and learn about its values.

The paper and this blog post are collaborative work between Ruijia “Regina” Cheng and Benjamin Mako Hill. The paper is being published this month(open access) in the Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction The full citation for this paper is: Ruijia Cheng and Benjamin Mako Hill. 2022. Many Destinations, Many Pathways: A Quantitative Analysis of Legitimate Peripheral Participation in Scratch. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 6, CSCW2, Article 381 (November 2022), 26 pages https://doi.org/10.1145/3555106

The paper is also available as an arXiv preprint and in the ACM Digital Library. The paper is being presented several times at the Virtual CSCW conference taking place in November 2022. Both Regina and Mako are happy to answer questions over email, in the comments on this blog post, or at the one remaining presentation slot at the CSCW conference on November 16th at 8-9pm Pacific Time.