In The Wealth Of Networks, Yochai Benkler describes the opportunities and decisions presented by networked forms of production. Writing in the mid-2000s, Benkler describes a wide range of future policy battlegrounds: copyrights and patents, common carrier infrastructure, the accessibility of the public sphere, and the verification of information.

Benkler predicts: “How these battles turn out over the next decade or so will likely have a significant effect on how we come to know what is going on in the world we occupy, and to what extent and in what forms we will be able…to affect how we and others see the world as it is and as it might be.”

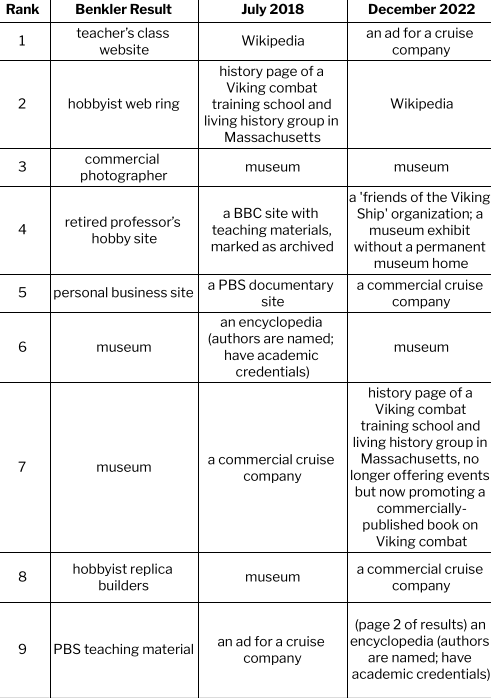

Benkler uses two simple search examples, reporting the results of searching for “Viking ship” and “Barbie”. He finds that enthusiastic individuals and independent voices dominate the content we see on the web and that various search engines construct meaning in varying ways. I repeat his examples (searches conducted 7/3/2018 and 12/1/2022, from my home near Seattle, WA and using my personal laptop).

So how do ‘we come to know what is going on in the world we occupy’? Who creates what we see online? And what implications does that have for our own freedom to shape the world? The short version of the answer to this question seems to be: if there was a battle, it’s over now and the wreckage has disappeared; individuals and independent voices are marginalized and commercial content is dominant — and this picture does not vary among search engines.

Viking Ships

I used the same search engine (Google) and the same term (Viking Ship): what I see is that the individual hobbyists Benkler saw in 2006 are eclipsed by institutions. The materials on the current sites sound similar to those Benkler saw – photos, replicas, and scholarly information, as well as links and learning materials – but the production is generally institutional and formal in contrast to the individual and informal sources Benkler reports.

One other shift: in 2022, simply listing links in order is not sufficient to report what searchers see. Search results are interspersed with many other features: a widget with “sources from across the web”, an images display with associated keywords, a “People also ask” widget, and a related searches widget; to reach the 9th “result” in the classic sense, I have to browse to the second page of results.

Barbie

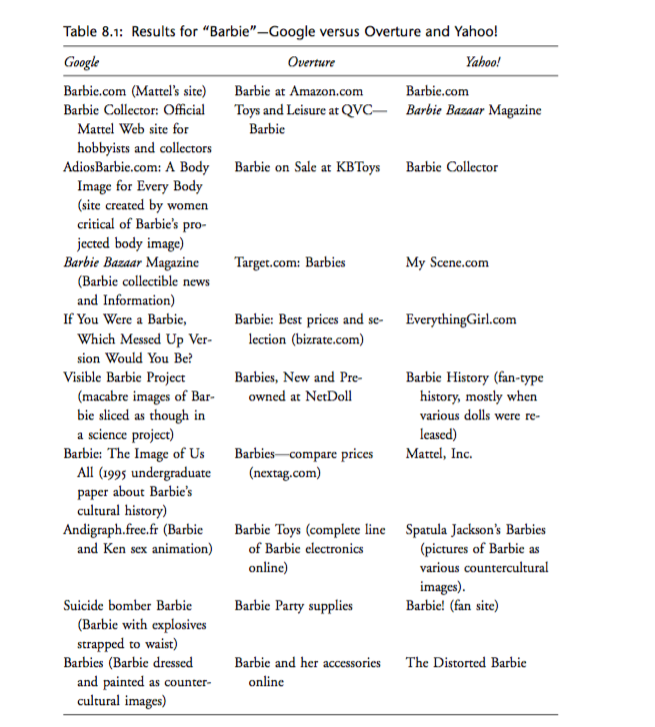

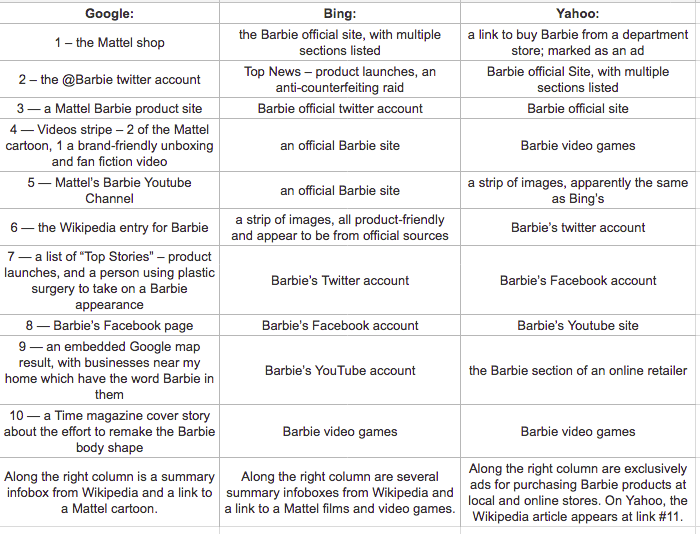

When I follow Benkler’s lead and search for ‘Barbie’ using three different search engines, the results are even more different from 2006. Benkler describes differences in search engine results as revealing different possibilities – via Google, Barbie was portrayed as “a culturally contested figure”, whereas on Overture (a now-defunct shopping-oriented search engine), the searcher encountered “a commodity toy.”

Here is Benkler’s figure 8, from page 286 of The Wealth of Networks:

By contrast, my 2018 search via the then-current top 3 search engines, inclusive of widgets and other features, revealed:

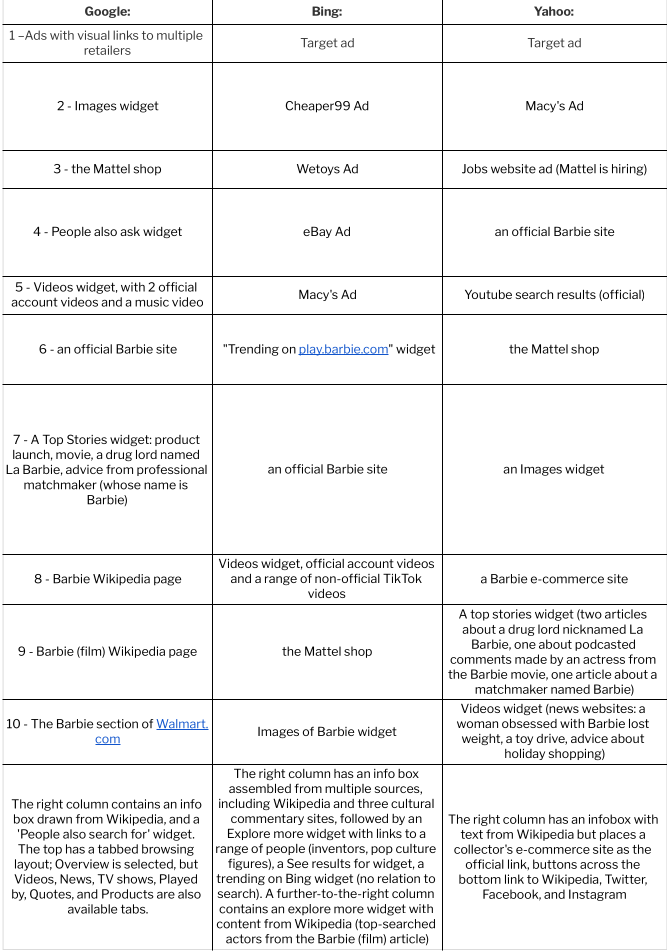

The top search engines in 2022 are the same three firms, although I observe that some sources suggest DuckDuckGo, Baidu (Chinese language only) and Yandex (Russian) belong in a top 5; other sources treat YouTube and Amazon as “top search engines” although they are not actually search engines. My 2022 search, inclusive of widgets and other features, revealed:

The modern Barbie searcher encounters primarily a multiplatform brand, with some hints of cultural constructions. In 2018 this took the form of extreme plastic surgery and brand-friendly fan fiction, in 2022 weight loss and fan TikTok. To whatever degree search engine algorithms continue to give weight to alternate voices in this case, they are largely drowned out by the volume of the commercial voice: the meaning of a search query for the single term “Barbie” has been substantially narrowed since Benkler’s time, and perhaps has narrowed even further in the last four and a half years.

The web in 2006 was indeed a different place, and I have commented on additional dimensions of analysis not present in Wealth: embedding of visual and social media content, and the widgetizing of content. In 2018, these visual components were less dominant: a stripe of Viking Ship images and a stripe of Barbie videos. In 2022 search, the page can scarcely be described without them.

We can now answer Benkler’s challenge: how did “these battles” over the last decade and a half “turn out”?

How do we “come to know what is going on in the world we occupy”?

How are we able “to affect how we and others see the world as it is and as it might be”?

The answer seems to be, it’s unclear to what degree there was a battle at all: collectives have triumphed over individuals on the Web insofar as search engines represent it. These collectives are generally firms, although some formal institutions are also present: news media, Wikipedia, and (in the case of Viking Ship) museums.

The implications of our search environment are significant, and underscore the necessity of efforts to archive and capture the search landscape as it appeared. The role of platforms and institutions in constructing our understanding of the world should be of key concern in information and communication sciences.

For civil society groups, these results suggest alienation: the commercializing of the web has been accompanied by a narrowing of outlets for individual expression and critique, with Wikipedia and its community co-construction of knowledge a vital bright spot. For journalists, these results suggest the vital role of cultural reporting. For firms, the challenge is one of authenticity and connection: to the extent that the web has become a broadcast medium focused on official paid messaging, the opportunity to engage with consumers is lost, and along with it a spark for innovation. Search platforms benefit in the mean time, as jockeying for ad positioning between manufacturers and retailers drives revenue, at least until commercialism turns consumer attention elsewhere.