Hundreds of new subreddits are created every day, but most of them go nowhere, and never receive more than a few posts or comments. On the other hand, some become wildly popular. If we want to figure out what helps some things to get attention, then looking at new and small online communities is a great place to start. Indeed, the whole focus of my dissertation was trying to understand who started new communities, and why. So, I was super excited when Sanjay Kairam at Reddit told me that Reddit was interested in studying founders of new subreddits!

The research that Sanjay and I (but mostly Sanjay!) did was accepted at CHI 2024, a leading conference for human-computer interaction research. The goal of the research is to understand 1) founders’ motivations for starting new subreddits, 2) founders’ goals for their communities, 3) founders’ plans for making their community successful, and 4) how all of these relate to what happens to a community in the first month of its existence. To figure this out, we surveyed nearly 1,000 redditors one week after they created a new subreddit.

Lots of Motivations and Goals

So, what did we learn? First, that founders have diverse motivations, but the most common is interest in the topic. As shown in the figure above, most founders reported being motivated by topic engagement, information exchange, and connecting with others, while self-promotion was much more rare.

When we asked about their goals for the community, founders were split, and each of the options we gave was ranked as a top goal by a good chunk of participants. While there is some nuance between the different versions of success, we grouped them into “quantity-oriented” and “quality-oriented”, and looked at how motivations related to goals. Somewhat unsurprisingly, folks interested in self-promotion had quantity-oriented goals, while those interested in exchanging information were more focused on quality.

Diversity in plans

We then asked founders about what plans they had for building their community, based on recommendations from the online community literature, such as raising awareness, welcoming newcomers, encouraging contributions, and regulating bad behavior. Surprisingly, for each activity, about half of people said they planned to engage in doing that thing.

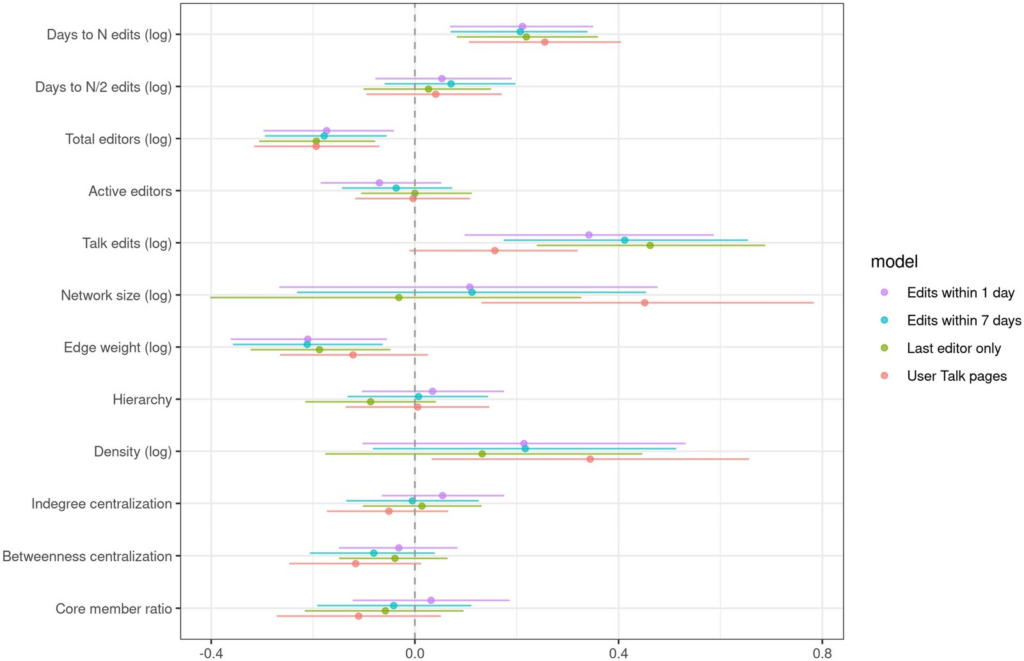

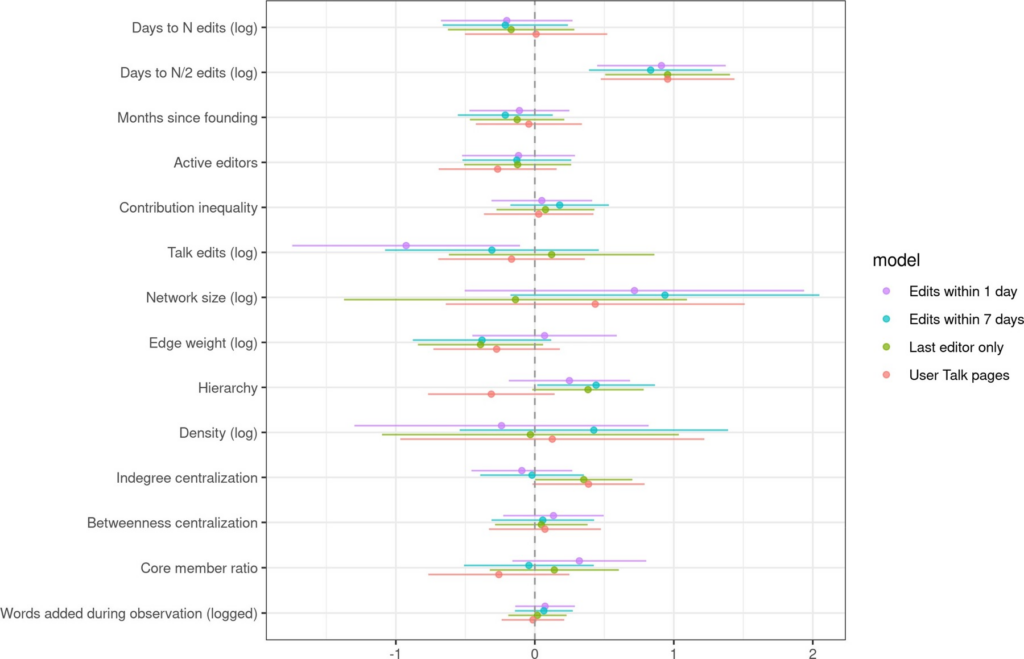

Early Community Outcomes

So, how do these motivations, goals, and plans relate to community outcomes? We looked at the first 28 days of each founded subreddit, and counted the number of visitors, number of contributors, and number of subscribers. We then ran regression analyses analyzing how well each aspect of motivations, goals, and plans predicted each outcome. High-level results and regression tables are shown below. For each row, when β is positive, that means that the given feature has a positive relationship with the given outcome. The exponentiated rate ratio (RR) column provides a point estimate of the effect size. For example, Self-Promotion has an RR of 1.32, meaning that if a given person’s self-promotion motivation was one unit higher the model predicts that their community would receive 32% more visitors.

A number of motivations predicted each of the outcomes we measured. The only consistently positive predictor was topical interest. Those who started a community because of interest in a topic had more visitors, more contributors, and more subscribers than others. Interestingly, those motivated by self-promotion had more visitors, but fewer contributors and subscribers.

Goals had a less pronounced relationship with outcomes. Those with quality-oriented goals had more contributors but fewer visitors than those with quantity-oriented goals. There was no significant difference in subscribers for founders with different types of goals.

Finally, raising awareness was the strategy most associated with our success metrics, predicting all three of them. Surprisingly, encouraging contributions was associated with more contributors, but fewer visitors. While we don’t know the mechanism for sure, asking for contributions seems to provide a barrier that discourages newcomers from taking interest in a community.

So what?

We think that there are some key takeaways for platform designers and those starting new communities. Sanjay outlined many of them on the Reddit engineering blog, but I’ll recap a few.

First, topical knowledge and passion is important. This isn’t a causal study, so we don’t know the mechanisms for sure, but people who are passionate about a topic may be aware of other communities in the space and are able to find the right niche; they are also probably better at writing the kinds of welcome messages, initial posts, etc. that appeal to people interested in the topic.

Second, our work is yet more evidence that communities require different things at different points in their lifecycle. Founders should probably focus on building awareness at first, and worry less about encouraging contributions or regulating behavior.

Finally, we think there are a lot of opportunities for designers to take diverse motivations and goals seriously. This could include matching people by their motivations for using a community, developing dashboards that capture different aspects of success and community health and quality, etc.

Learn More

If you want to learn more about the paper, you have options!

- If you’re at CHI, come to the talk. It will be at 9:45 in room 319 on Tuesday, May 14

- Read the paper (and cite it)!

- Join the conversation on Reddit ( r/RedditEng, r/CompSocial)

- Talk with Sanjay and me on social media