Although the world relies on free/libre open source software (FLOSS) for essential digital infrastructure such as the web and cloud, the software that supports that infrastructure are not always as high quality as we might hope, given our level of reliance on them. How can we find this misalignment of quality and importance (or underproduction) before it causes major failures?

How can we find misalignment of quality and importance (underproduction) before it causes major failures?

In previous work, we found that underproduction is widespread in packages maintained by the Debian community, and when we shared this work in the Debian and FLOSS community, developers suggested that the age and language of the packages might be a factor, and tech managers suggested looking at the teams doing the maintenance work. Software engineering literature had found some support for these suspicions as well, and we embarked on a study to dig deeper into some of the factors associated with underproduction.

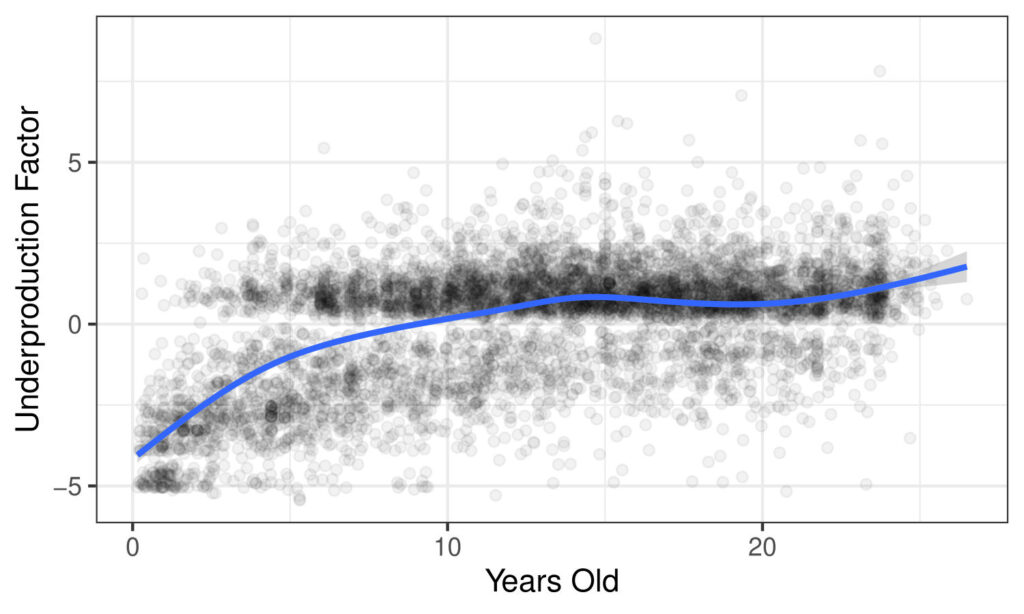

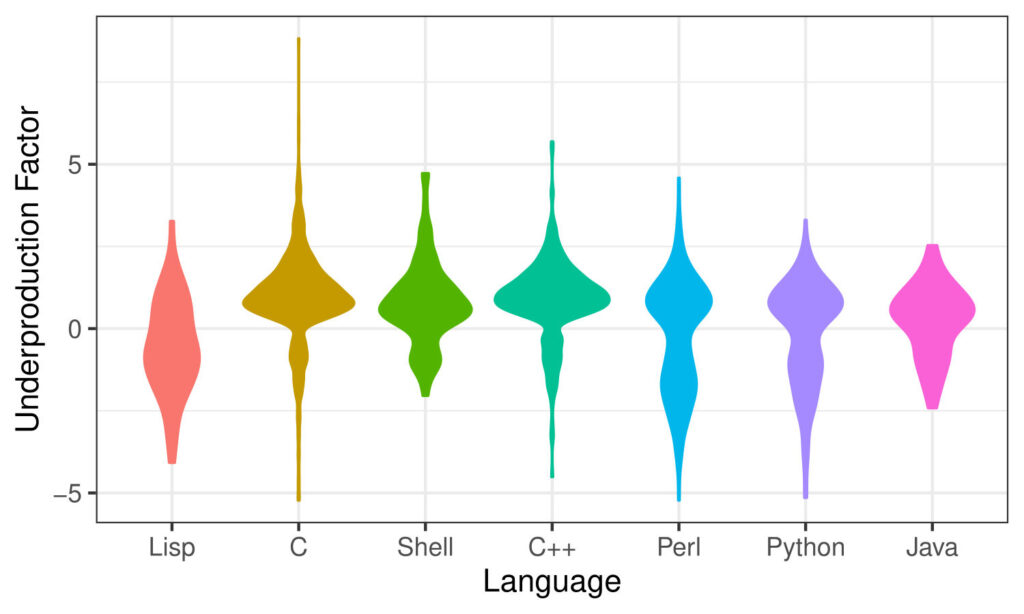

Our study was able to partially confirm this perspective using the underproduction analysis dataset from our previous study: software risk due to underproduction increases with age of both the package and its language, although many older packages and those written in older languages are and continue to be very well-maintained.

In this plot, dots represent software packages and their age, with higher underproduction factor indicating higher risk. The blue line is a smoothed average: note that we see an increase over time initially, but the trend flattens out for older packages.

This plot shows the spread of the data across the range of underproduction factor, grouped by language, where higher values are indications of higher risk. Languages are sorted from oldest on the left (Lisp) to youngest on the right (Java). Although newer languages overall are associated with lower risk, we see a great deal of variation.

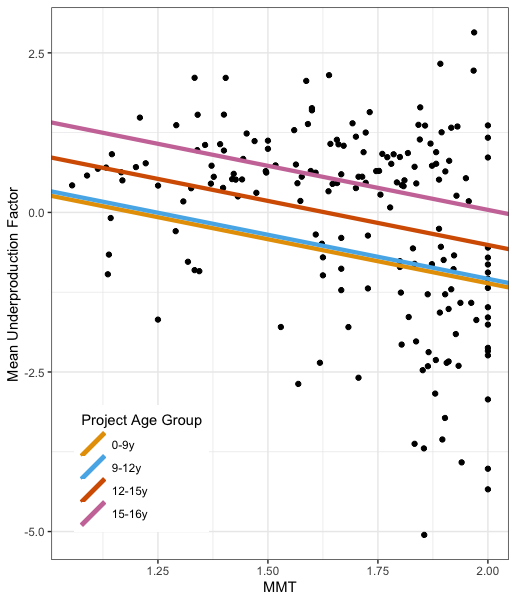

However, we found the resource question more complex: additional contributors were associated with higher risk instead of decreasing it as we hypothesized. We also found that underproduction is associated with higher eigenvector centrality in the network formed if we take packages as nodes and edges by having shared maintainers; that is, underproduced packages were likely to be maintained by the same people maintaining other parts of Debian, and not isolated efforts. This suggests that these high-risk packages are drawing from the same resource pool as those which are performing well. A lack of turnover in maintainership and being maintained by a team were not statistically significant once we included maintainer network structure and age in our model.

How should software communities respond? Underproduction appears in part to be associated with age, meaning that all communities sooner or later may need to confront it, and new projects should be thoughtful about using older languages. Distributions and upstream project developers are all part of the supply chain and have a role to play in the work of preventing and countering underproduction. Our findings about resources and organizational structure suggest that “more eyeballs” alone are not the answer: supporting key resources may be of particular value as a means to counter underproduction.

This paper will be presented as part of the International Conference on Software Analysis, Evolution and Reengineering (SANER) 2024 in Rovaniemi, Finland. Preprint available HERE; code and data released HERE.

This work would not have been possible without the generosity of the Debian community. We are indebted to these volunteers who, in addition to producing Free/Libre Open Source Software software, have also made their records available to the public. We also gratefully acknowledge support from the Sloan Foundation through the Ford/Sloan Digital Infrastructure Initiative, Sloan Award 2018-11356 as well as the National Science Foundation (Grant IIS-2045055). This work was conducted using the Hyak supercomputer at the University of Washington as well as research computing resources at Northwestern University.