While Wikipedia is famous for its encyclopedic content, it may be surprising to realize that a whole other set of pages on Wikipedia help guide and govern the creation of the peer-produced encyclopedia. These pages extensively describe processes, rules, principles, and technical features of creating, coordinating, and organizing on Wikipedia. Because of the success of Wikipedia, these pages have provided valuable insights into how platforms might decentralize and facilitate participation in online governance. However, each language edition of Wikipedia has a unique set of such pages governing it respectively, even though they are part of the same overarching project: in other words, an under-explored opportunity to understand how governance operates across diverse groups.

In a manuscript published at ICWSM2022, we present descriptive analyses examining on rules and rule-making across language editions of Wikipedia motivated by questions like:

What happens when communities are both relatively autonomous but within a shared system? Given that they’re aligned in key ways, how do their rules and rule-making develop over time? What can patterns in governance work tell us about how communities are converging or diverging over time?

We’ve been very fortunate to share this work with the Wikimedia community since publishing the paper, such as the Wikipedia Signpost and Wikimedia Research Showcase. At the end of last year, we published the replication data and files on Dataverse after addressing a data processing issue we caught earlier in the year (fortunately, it didn’t affect the results – but yet another reminder to quadruple-check one’s data pipeline!). In the spirit of sharing the work more broadly since the Dataverse release, we summarize some of the key aspects of the work here.

Study design

In the project, we examined the five largest language editions of Wikipedia as distinct editing communities: English, German, Spanish, French and Japanese. After manually constructing lists of rules per wiki (resulting in 780 pages), we took advantage of two features on Wikipedia: the revision histories, which log every edit to every page; and the interlanguage links, which connect conceptually equivalent pages across language editions. We then conducted a series of analyses examining comparisons across and relationships between language editions.

Shared patterns across communities

Across communities, we observed that trends suggested that rule-making often became less open over time:

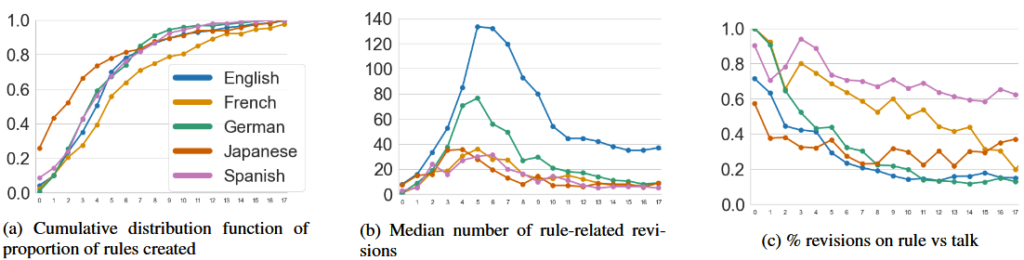

- Most rules are created early in the life of the language edition community’s life. Over a nearly 20 year period, roughly 50-80% of the rules (depending on the language edition) were created within the first five years!

- The median edit count to rule pages peaked in early years (between years 3 and 5) before tapering down. The percent of revisions dedicated to editing the actual rule text versus discussing it shifts towards discussion of rule across communities. These both suggest that rules across communities have calcified over time.

Said simply, these communities have very similar trends in rule-making towards formalization.

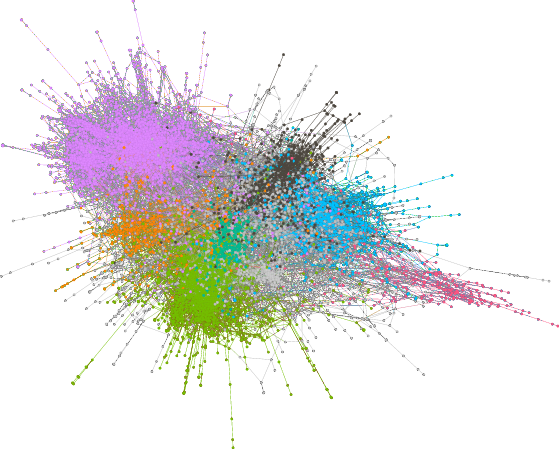

Divergence vs convergence in rules

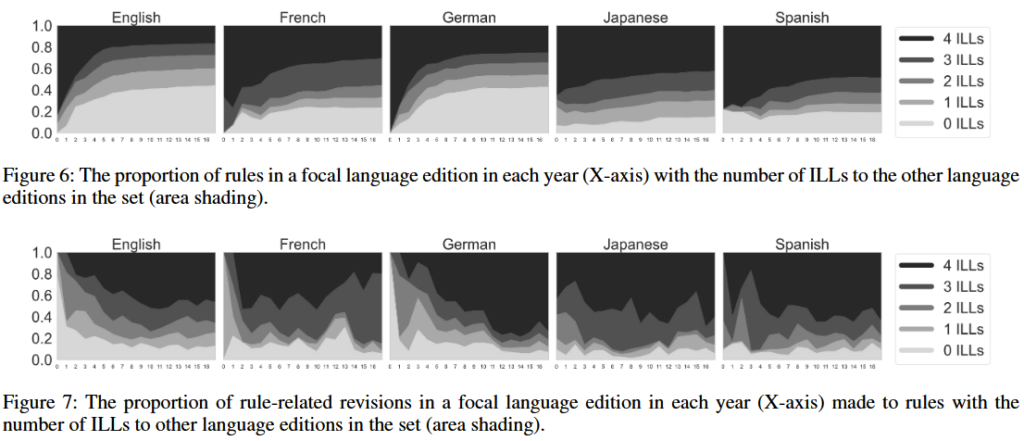

Wikipedia’s interlanguage link (ILL) feature, as mentioned above, lets us explore how the rules being created and edited on communities relate to one another. While the trends above highlight similarities in rule-making, here, the picture about how the rule sets are similar or not is a bit more complicated.

On one hand, the top panel here shows that over time, all five communities see an increase in the proportion of rules in their rules sets that are unique to them individually. On the other hand, the bottom panel shows that editing efforts concentrate on rules that are more shared across communities.

Altogether, we see that communities sharing goals, technology, and a lot more develop substantial and sustained institutional variations; but it’s possible that broad, widely-shared rules created early may help keep them relatively aligned.

Key takeaways

Investigating governance across groups like Wikipedia is valuable for at least two reasons.

First, an enormous amount of effort has gone into studying governance on English Wikipedia, the largest and oldest language edition, to distill lessons about how we can meaningfully decentralize governance in online spaces. But, as prior work [e.g., 1] shows, language editions are often non-aligned in both the content they produce and how they organize that content. Some early stage work we did noted this held true for rule pages on the five language editions of Wikipedia explored here. In recent years, the Wikimedia Foundation itself has made several calls to understand dynamics and patterns beyond English Wikipedia. This work is in part in response to this movement.

Second, the questions explored in our work highlight a key tension in online governance today. While online communities are relatively autonomous entities, they often exist within social and technical systems that put them in relation with one another – whether directly or not. Effectively addressing concerns about online governance means understanding how distinct spaces online govern in ways that are similar or dissimilar, overlap or conflict, diverge and converge. Wikipedia can offer many lessons to this end because it has an especially decentralized and participatory vision of how to govern itself online, such as how patterns of formalization impact success and engagement. Future work we are working on continues in this vein – stay tuned!