Everyone knows that making friends can be a bit daunting as a new student (especially international or if you’re not from the area). With that in mind, a while after I arrived in Chicago to begin my PhD program last Fall, a Brazilian friend and I made a Northwestern WhatsApp group for international graduate students! Since the point of the group was to make friends, we were pretty laid back in there (still are!), and people mostly shared events across campus and the city of Evanston and Chicago – especially those offering free food.

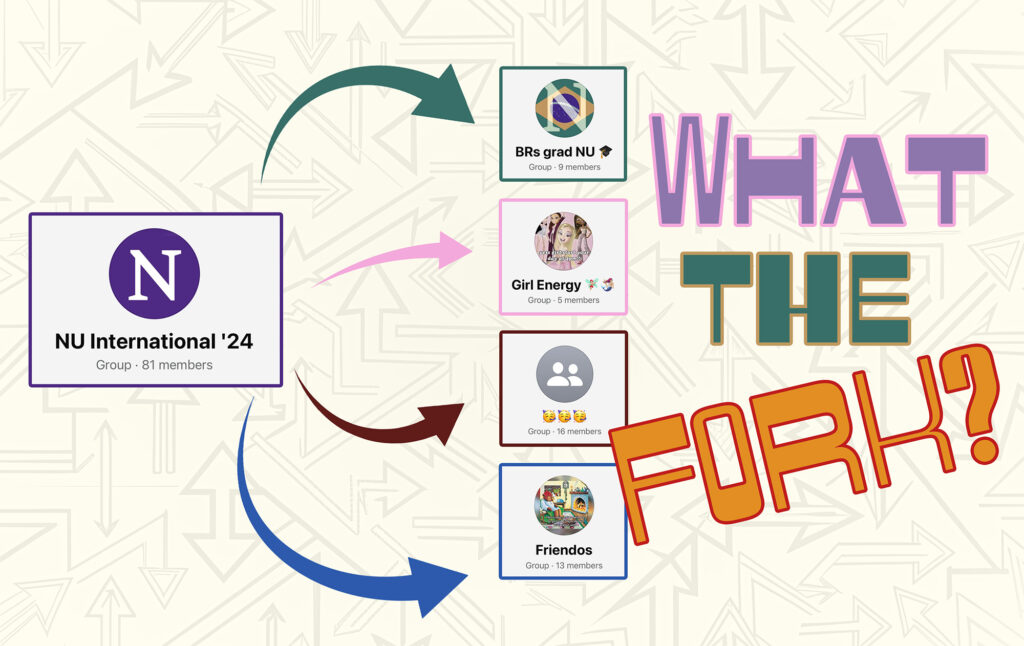

At some point, the group started to grow fast, and my friend and I lost track of people who were joining. It reached 81(!) members. Eventually, we started to make sub-groups. First, we made a group for the Brazilian grad students; then another group was made for the women called “Girl Energy”; later, one of my friends made a group only for Latinos (the name is interestingly only “🥳🥳🥳”). Lastly, the group “Friendos” emerged, including our guy friends this time!

After a while, activity on the all international grad students group died down. It goes weeks without a message. People have basically spread out into smaller groups. Now… Why is that?

I went to my advisor (Aaron Shaw) and we basically started geeking out. I didn’t plan on doing some random experiment, but I accidentally observed what is called a “fork” of online communities!

To better explain this, let’s go back to the 1970s. Albert O. Hirschman published the influential book Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States. In the book, Hirschman makes the argument that consumers can show their dissatisfaction in two ways: they can either exit (stop using that service or buying that product) or they can use voice (communicate a complaint and try to suggest a change). The simplicity of this argument makes it applicable in a range of different fields, such as “personal relationships, emigration, workplace relations, political parties, as well as public policy” (Dowding, 2016). And, more recently, online communities!

There are a lot of works based on Hirschman’s book, and mostly recently the idea of “fork” has also been added as a concept together with exit and voice:

“Forking is a form of group secession (exit) that takes an existing set of institutions and creates a new ‘society’ with a shared history but divergent futures.” (Berg and Berg, 2020)

The term originally comes from open source software communities, where developers are allowed to copy a code repository, work on it separately, modify it, and release it in different forms. Seeing it this way, it makes a lot of sense that it could be applied to online communities as well. In fact, studies related to online community migration keep growing. For example, Fiesler and Dym (2020) explored how transformative fandom communities migrate across platforms over a period of 20 years. Migration was driven by changes in platform policies, user needs, or technical issues. Their work highlights how these migrations can lead to social fragmentation, the loss of shared cultural artifacts, and the reformation of communities in new spaces.

In our case, the international graduate students’ group provided the foundation for forming meaningful connections. However, as people developed closer friendships and found more specific communities of interest (e.g., Brazilian grad students or Girl Energy), the need for the larger, general group diminished. This isn’t necessarily a sign of failure for the original community but rather an indication of its success in fulfilling its initial purpose!

It’s fascinating to observe how the lifecycle of online communities can parallel theoretical concepts like Hirschman’s exit, voice, and loyalty and grow from there. These frameworks help explain not just why communities evolve but also how users actively shape their social environments to meet their changing needs. Have you noticed similar patterns in the communities you’re a part of?

Discover more from Community Data Science Collective

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.