Inequality and discrimination in the labor market is a persistent and sometimes devastating problem for job seekers. Increasingly, labor is moving to online platforms, but labor inequality and discrimination research often overlooks work that happens on such platforms. Do research findings from traditional labor contexts generalize to the online realm? We have reason to think perhaps not, since entering the online labor market requires specific technical infrastructure and skills (as we showed in this paper). Besides, hiring processes for online platforms look significantly different: these systems use computational structures to organize labor at a scale that exceeds any hiring operation in the traditional labor market.

To understand what research on patterns of inequality and discrimination in the gig economy is out there and to identify remaining puzzles, I (Floor) systematically gathered, analyzed, and synthesized studies on this topic. The result is a paper recently published in New Media & Society.

I took a systematic approach in order to capture all the different strands of inquiry across various academic fields. These different strands might use different methods and even different language but, crucially, still describe similar phenomena. For this review, Siying Luo (research assistant on this project) and I gathered literature from five academic databases covering multiple disciplines. By sifting through many journal articles and conference proceedings, we identified 39 studies of participation and success in the online labor market.

Most research focuses on individual-level resources and biases as a source of unequal participation, rather than the role of the platform.

Three approaches

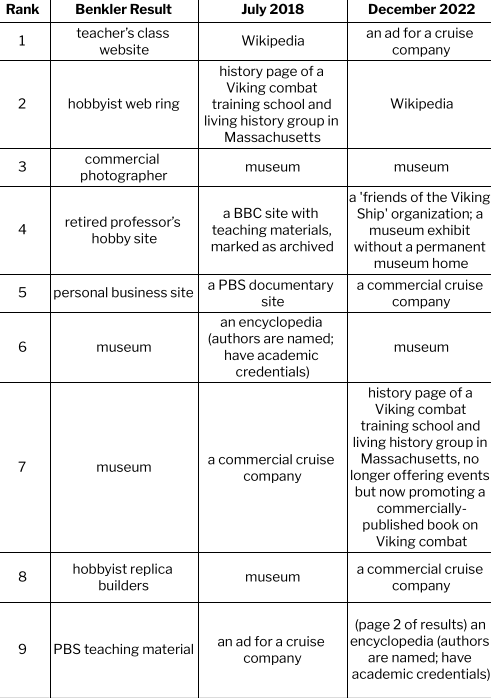

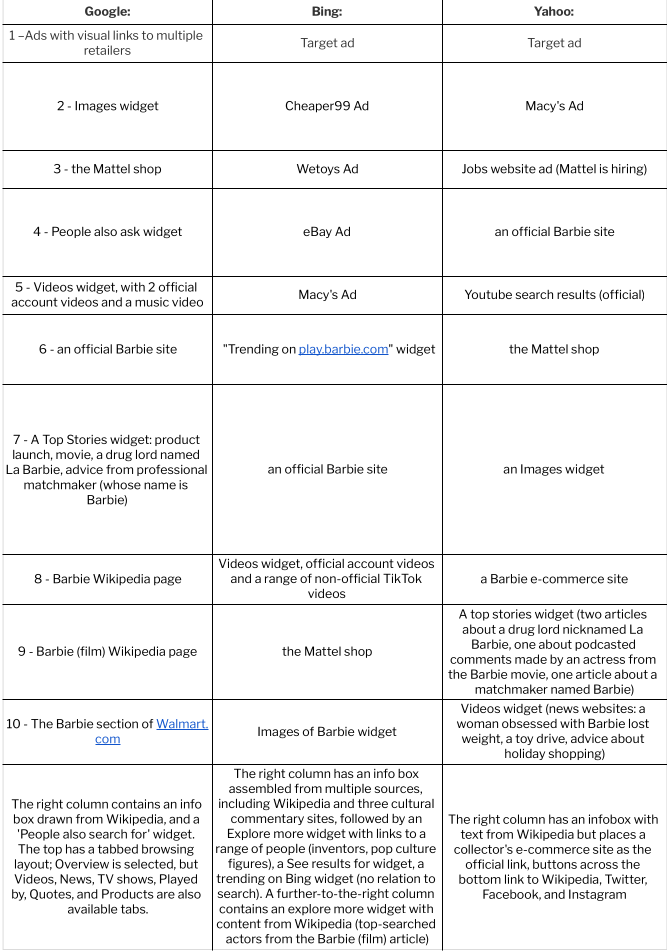

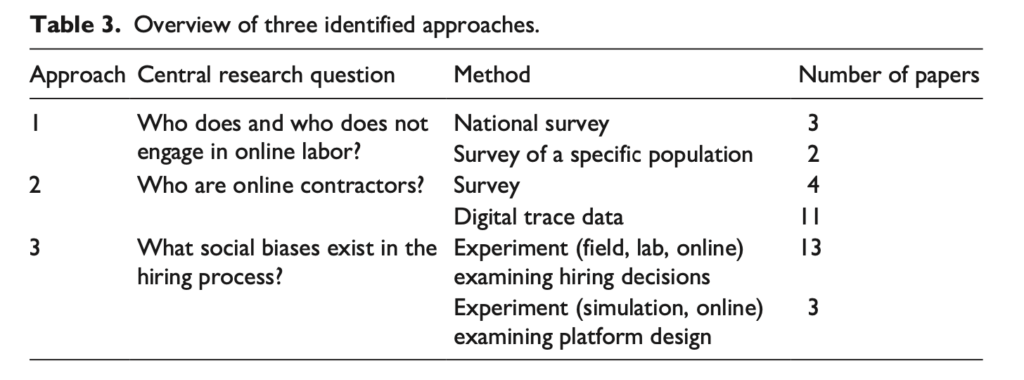

I found three approaches to the study of inequality and discrimination in the gig economy. All address distinct research questions drawing on different methods and framing (see the table below for an overview).

Approach 1 asks who does and who does not engage in online labor. This strand of research takes into account the voices of both those who have pursued such labor and those who have not. Five studies take this approach, of which three draw on national survey data and two others examine participation among a specific population (such as older adults).

Approach 2 asks who online contractors are. Some of this research describes the sociodemographic composition of contractors by surveying them or by analyzing digital trace data. Other studies focus on labor outcomes, identifying who among those that pursue online labor actually land jobs and generate an income. You might imagine a study asking whether male contractors make more money on an online platform than female contractors do.

Approach 3 asks what social biases exist in the hiring process, both on the side of individual users making hiring decisions and the algorithms powering the online labor platforms. Studies taking this approach tend to rely on experiments that test the impact of some manipulation in the contractor’s sociodemographic background on an outcome, such as whether they get featured by the platform or whether they get hired.

Extended pipeline of online participation inequalities

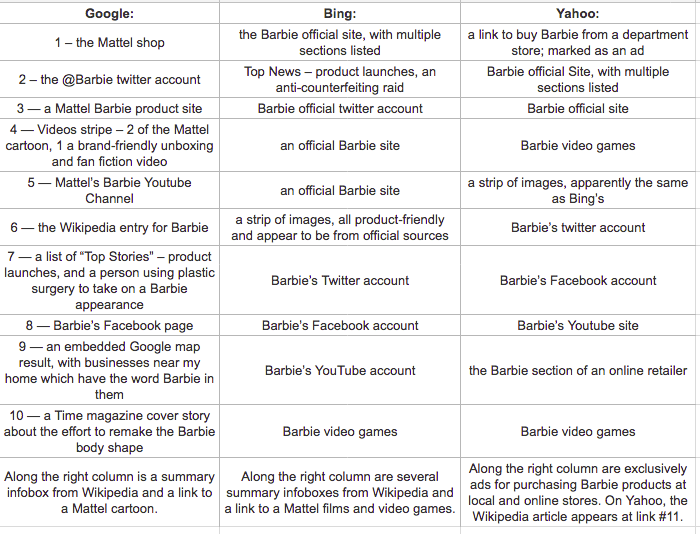

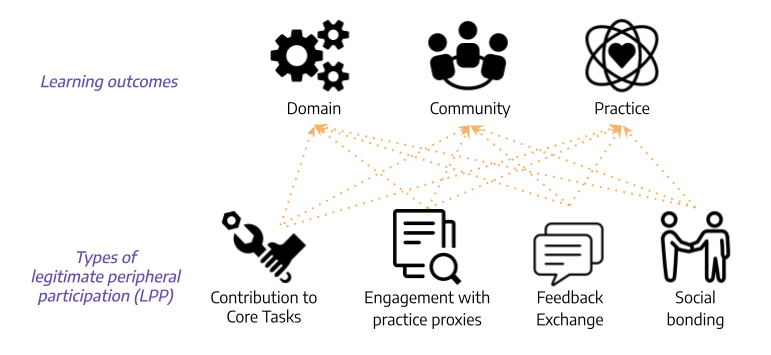

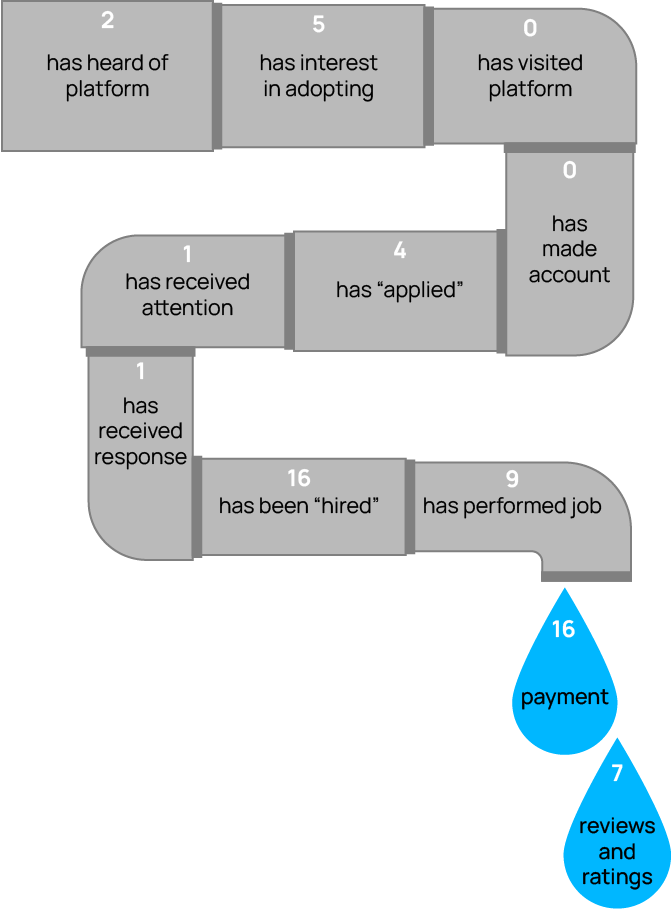

In addition to identifying these three approaches, I map the outcomes variables of all studies across an extended version of the so-called pipeline of participation inequalities (as coined and tested in this paper). This model breaks down the steps one needs to take before being able to contribute online, presenting them in the form of a pipeline. Studying online participation as stages of the pipeline allows for the identification of barriers since it reveals the spots where people face obstacles and drop out before fully participating. Mapping the literature on inequality and discrimination in the gig economy across stages of a pipeline proved helpful in understanding and visualizing what parts of the process of becoming an online contractor have been studied and what parts require more attention.

I extended the pipeline of participation inequalities to fit the process of participating in the gig economy. This form of online participation does not only require having the appropriate access and skills to participate, but also requires garnering attention and getting hired. The extended pipeline model has eleven stages: from having heard of a platform to receiving payment as well as reviews and ratings for having performed a job. The figure below shows a visualization of the pipeline with the number of studies that study an outcome variable associated with each stage.

When mapping the studies across the pipeline, we find that two stages have been studied much more than others. Prior literature primarily examines whether individuals who pursue work online are getting hired and receiving a payment. In contrast, the literature in this scoping review hardly examined earlier stages of the pipeline.

So, what should we take away?

After systematically gathering and analyzing the literature on inequality and discrimination in the online labor market, I want to highlight three takeaways.

One: Most of the research focuses on individual-level resources and biases as a source of unequal participation. This scoping review points to a need for future research to examine the specific role of the platform in facilitating inequality and discrimination.

Two: The literature thus far has primarily focused on behaviors at the end of the pipeline of participation inequalities (i.e., having been hired and received payment). Studying earlier stages is important as it might explain patterns of success in later stages. In addition, such studies are also worthwhile inquiries in their own right. Insights into who meets these conditions of participation and desired labor outcomes are valuable, for example, in designing policy interventions.

Three: Hardly any research looks at participation across multiple stages of the pipeline. Considering multiple stages in one study is important to identify the moments that individuals face obstacles and how sociodemographic factors relate to making it from one stage to the next.

For more details, please find the full paper here.

Floor Fiers is PhD candidate at Northwestern University in the Media, Technology, and Society program. They received support and advice from other members of the collective. Most notably, Siying Luo contributed greatly to this project as a research assistant.