I’ve heard a surprising “fact” repeated in the CHI and CSCW communities that receiving a best paper award at a conference is uncorrelated with future citations.

Although it’s surprising and counterintuitive, it’s a nice thing to

think about when you don’t get an award and its a nice thing to say to

others when you do. I’ve thought it and said it myself.

It also seems to be untrue. When I tried to check the “fact”

recently, I found a body of evidence that suggests that computing papers

that receive best paper awards are, in fact, cited more often than

papers that do not.

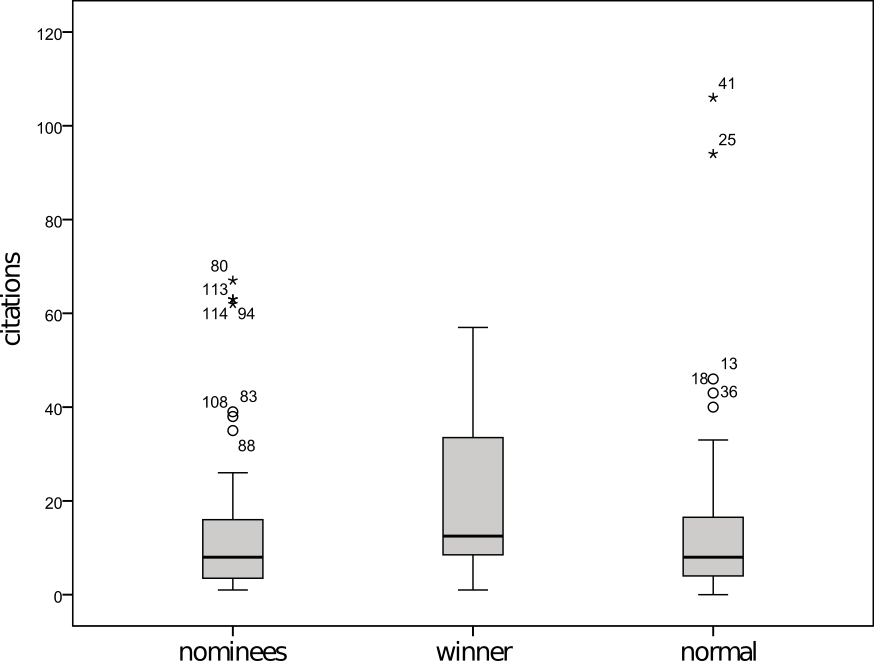

The source of the original “fact” seems to be a CHI 2009 study by Christoph Bartneck and Jun Hu titled “Scientometric Analysis of the CHI Proceedings.”

Among many other things, the paper presents a null result for a test of

a difference in the distribution of citations across best papers

awardees, nominees, and a random sample of non-nominees.

Although the award analysis is only a small part of Bartneck and Hu’s

paper, there have been at least two papers have have subsequently

brought more attention, more data, and more sophisticated analyses to

the question. In 2015, the question was asked by Jaques Wainer, Michael

Eckmann, and Anderson Rocha in their paper “Peer-Selected ‘Best Papers’—Are They Really That ‘Good’?“

Wainer et al. build two datasets: one of papers from 12 computer

science conferences with citation data from Scopus and another papers

from 17 different conferences with citation data from Google Scholar.

Because of parametric concerns, Wainer et al. used a non-parametric

rank-based technique to compare awardees to non-awardees. Wainer et al.

summarize their results as follows:

The probability that a best paper

will receive more citations than a non best paper is 0.72 (95% CI =

0.66, 0.77) for the Scopus data, and 0.78 (95% CI = 0.74, 0.81) for the

Scholar data. There are no significant changes in the probabilities for

different years. Also, 51% of the best papers are among the top 10% most

cited papers in each conference/year, and 64% of them are among the top

20% most cited.

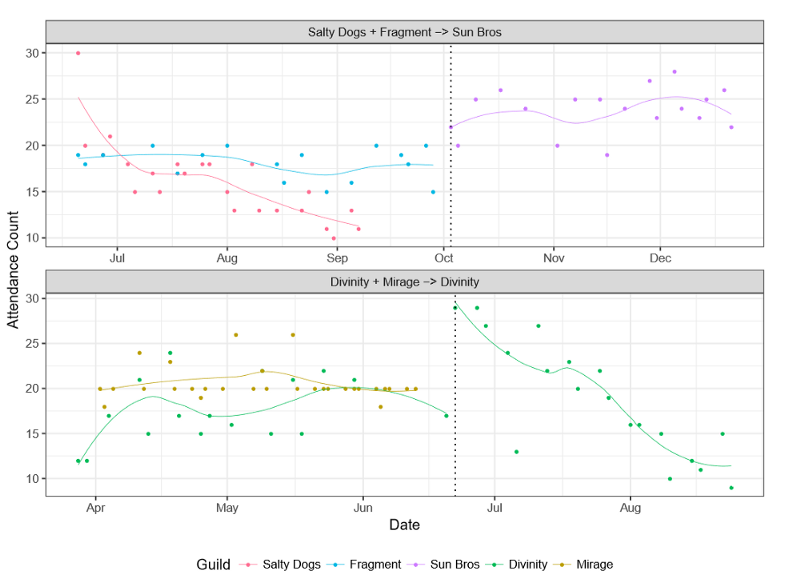

The question was also recently explored in a different way by Danielle H. Lee in her paper on “Predictive power of conference‐related factors on citation rates of conference papers” published in June 2018.

Lee looked at 43,000 papers from 81 conferences and built a

regression model to predict citations. Taking into an account a number

of controls not considered in previous analyses, Lee finds that the

marginal effect of receiving a best paper award on citations is

positive, well-estimated, and large.

Why did Bartneck and Hu come to such a different conclusions than later work?

My first thought was that perhaps CHI is different than the rest of

computing. However, when I looked at the data from Bartneck and Hu’s

2009 study—conveniently included as a figure in their original study—you

can see that they did find a higher mean among the award

recipients compared to both nominees and non-nominees. The entire

distribution of citations among award winners appears to be pushed

upwards. Although Bartneck and Hu found an effect, they did not find a statistically significant effect.

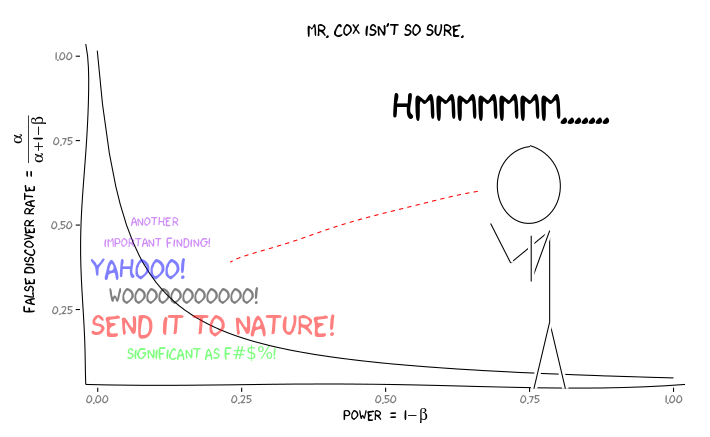

Given the more recent work by Wainer et al. and Lee, I’d be willing

to venture that the original null finding was a function of the fact

that citations is a very noisy measure—especially over a 2-5

post-publication period—and that the Bartneck and Hu dataset was small

with only 12 awardees out of 152 papers total. This might have caused

problems because the statistical test the authors used was an omnibus

test for differences in a three-group sample that was imbalanced heavily

toward the two groups (nominees and non-nominees) in which their

appears to be little difference. My bet is that the paper’s conclusions

on awards is simply an example of how a null effect is not evidence of a

non-effect—especially in an underpowered dataset.

Of course, none of this means that award winning papers are better.

Despite Wainer et al.’s claim that they are showing that award winning

papers are “good,” none of the analyses presented can disentangle the

signalling value of an award from differences in underlying paper

quality. The packed rooms one routinely finds at best paper sessions at

conferences suggest that at least some additional citations received by

award winners might be caused by extra exposure caused by the awards

themselves. In the future, perhaps people can say something along these

lines instead of repeating the “fact” of the non-relationship.

This post was originally posted on Benjamin Mako Hill’s blog Copyrighteous.

The

The