Many online platforms are adopting machine learning as a tool to maintain order and high quality information in the face of massive influxes of of user generated content. Of course, machine learning algorithms can be inaccurate, biased or unfair. How do signals from machine learning predictions shape the fairness of online content moderation? How can we measure an algorithmic flagging system’s effects?

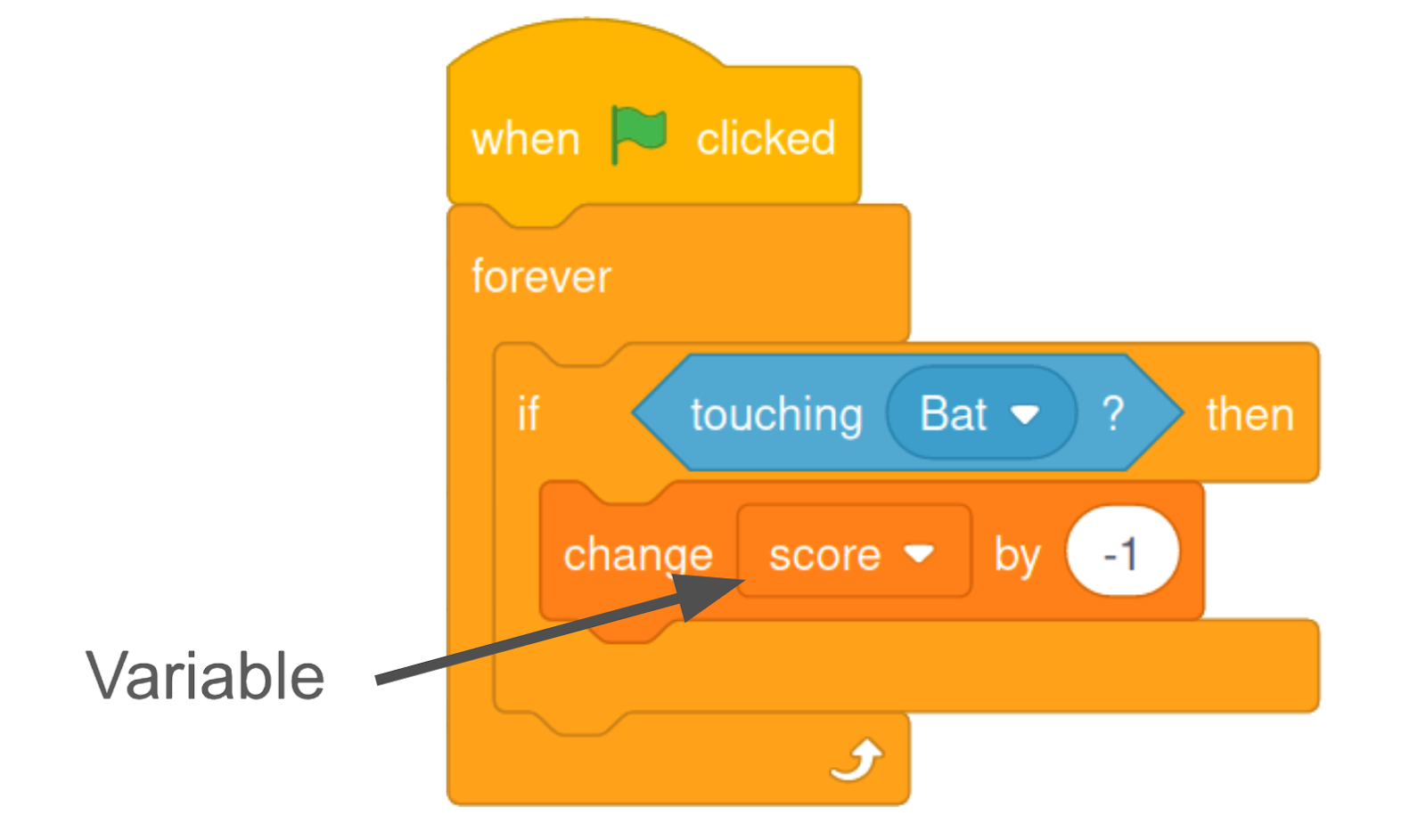

In our paper published at CSCW 2021, I (Nate TeBlunthuis) together with Benjamin Mako Hill and Aaron Halfaker analyzed the RCFilters system: an add-on to Wikipedia that highlights and filters edits that a machine learning algorithm called ORES identifies as likely to be damaging to Wikipedia. This system has been deployed on large Wikipedia language editions and is similar to other algorithmic flagging systems that are becoming increasingly widespread. Our work measures the causal effect of being flagged in the RCFilters user interface.

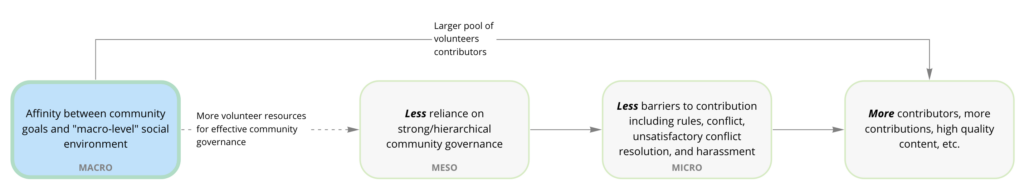

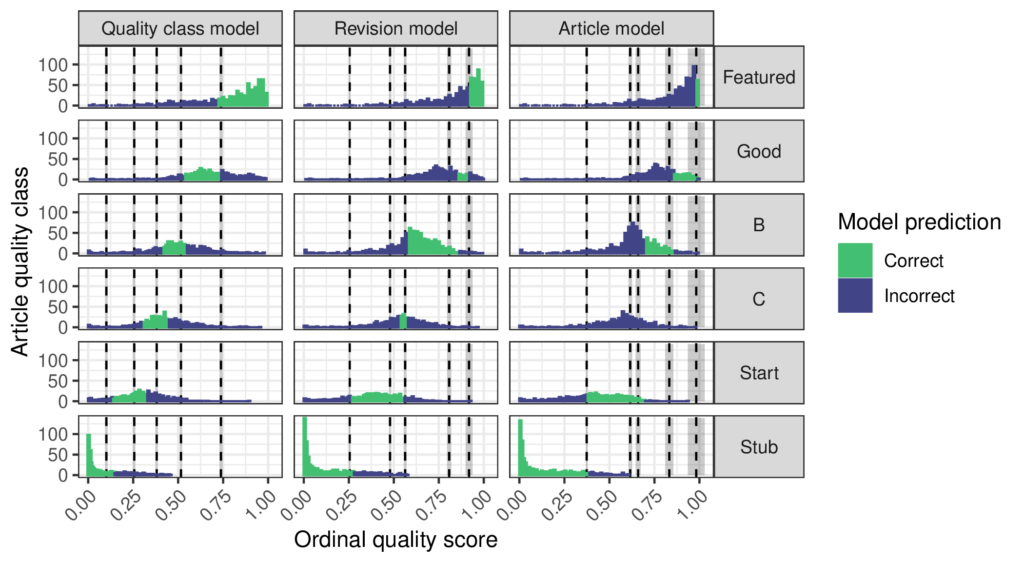

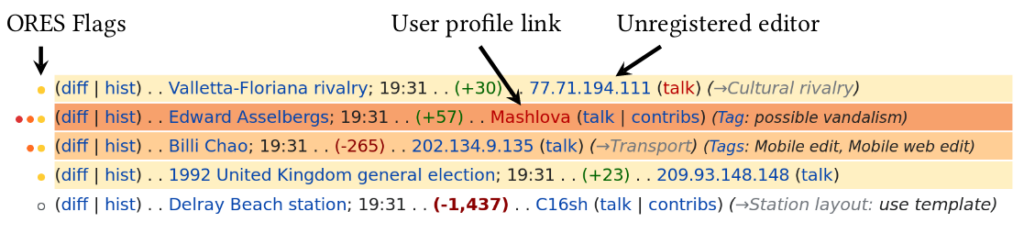

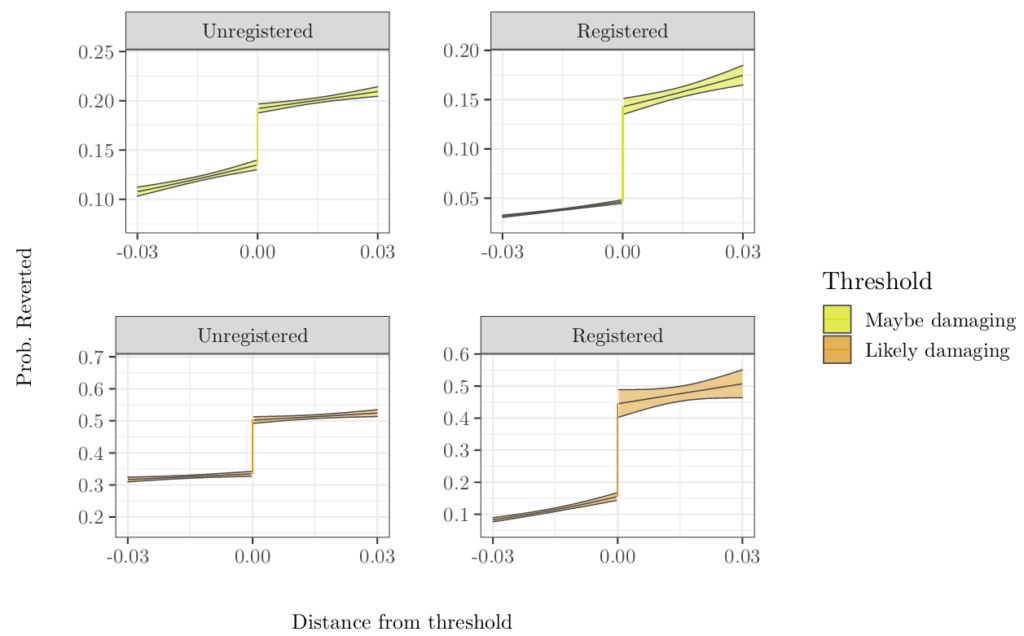

Our work takes advantage of the fact that RCFilters, like many algorithmic flagging systems, create discontinuities in the relationship between the probability that a moderator should take action and whether a moderator actually does. This happens because the output of machine learning systems like ORES is typically a continuous score (in RCFilters, an estimated probability that a Wikipedia edit is damaging), while the flags (in RCFilters, the yellow, orange, or red highlights) are either on or off and are triggered when the score crosses some arbitrary threshold. As a result, edits slightly above the threshold are both more visible to moderators and appear more likely to be damaging than edits slightly below. Even though edits on either side of the threshold have virtually the same likelihood of truly being damaging, the flagged edits are substantially more likely to be reverted. This fact lets us use a method called regression discontinuity to make causal estimates of the effect of being flagged in RCFilters.

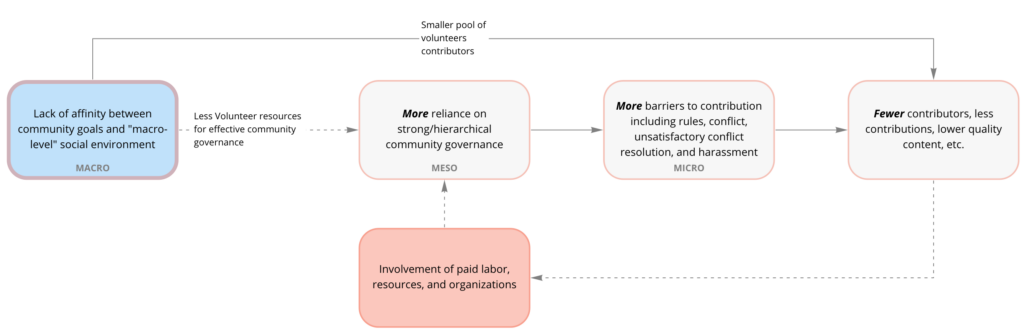

To understand how this system may effect the fairness of Wikipedia moderation, we estimate the effects of flagging on edits on different groups of editors. Comparing the magnitude of these estimates lets us measure how flagging is associated with several different definitions of fairness. Surprisingly, we found evidence that these flags improved fairness for categories of editors that have been widely perceived as troublesome—particularly unregistered (anonymous) editors. This occurred because flagging has a much stronger effect on edits by the registered than on edits by the unregistered.

We believe that our results are driven by the fact algorithmic flags are especially helpful for finding damage that can’t be easily detected otherwise. Wikipedia moderators can see the editor’s registration status in the recent changes, watchlists, and edit history. Because unregistered editors are often troublesome, Wikipedia moderators’ attention is often focused on their contributions, with or without algorithmic flags. Algorithmic flags make damage by registered editors (in addition to unregistered editors) much more detectable to moderators and so help moderators focus on damage overall, not just damage by suspicious editors. As a result, the algorithmic flagging system decreases the bias that moderators have against unregistered editors.

This finding is particularly surprising because the ORES algorithm we analyzed was itself demonstrably biased against unregistered editors (i.e., the algorithm tended to greatly overestimate the probability that edits by these editors were damaging). Despite the fact that the algorithms were biased, their introduction could still lead to less biased outcomes overall.

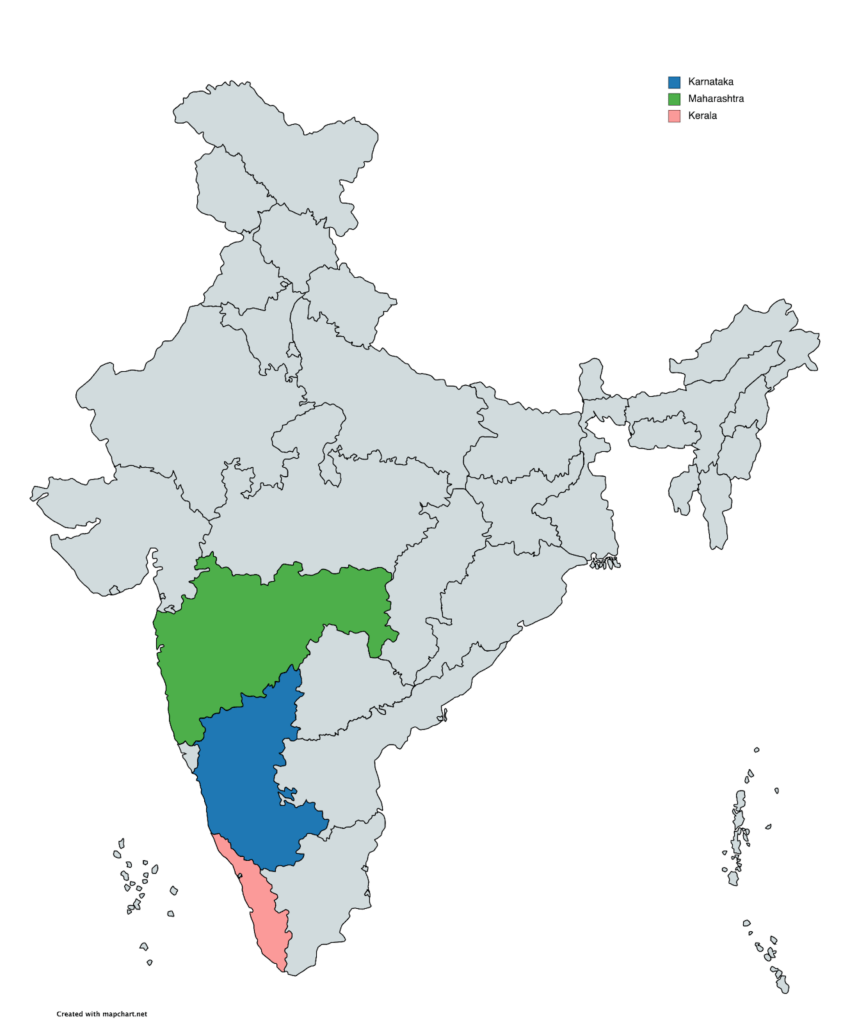

Our work shows that although it is important to design predictive algorithms to not have such biases, it is equally important to study fairness at the level of the broader sociotechnical system. Since we first published a preprint of our paper, a followup piece by Leijie Wang and Haiyi Zhu replicated much of our work and showed that differences between different Wikipedia communities may be another important factor driving the effect of the system. Overall, this work suggests that social signals and social context can interact with algorithmic signals and together these can influence behavior in important and unexpected ways.

The full citation for the paper is: TeBlunthuis, Nathan, Benjamin Mako Hill, and Aaron Halfaker. 2021. “Effects of Algorithmic Flagging on Fairness: Quasi-Experimental Evidence from Wikipedia.” Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction 5 (CSCW): 56:1-56:27. https://doi.org/10.1145/3449130.

We have also released replication materials for the paper, including all the data and code used to conduct the analysis and compile the paper itself.