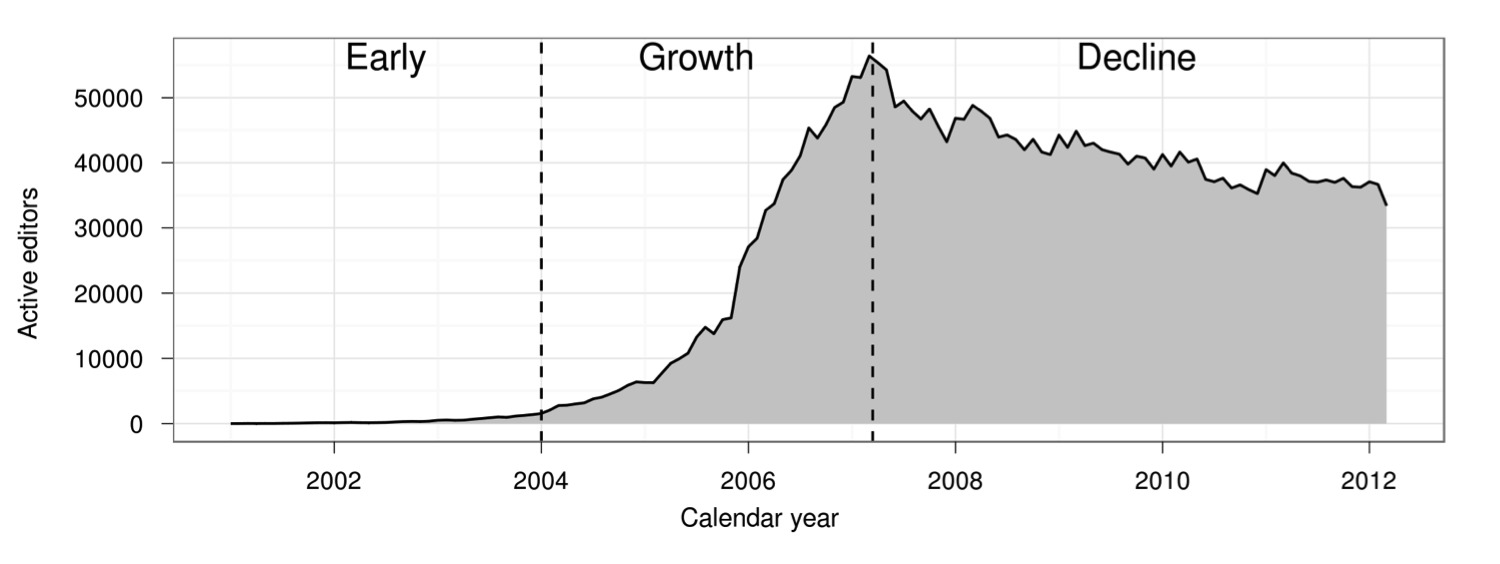

This graph shows the number of people contributing to Wikipedia over time:

The figure comes from “The Rise and Decline of an Open Collaboration System,” a well-known 2013 paper that argued that Wikipedia’s transition from rapid growth to slow decline in 2007 was driven by an increase in quality control systems. Although many people have treated the paper’s finding as representative of broader patterns in online communities, Wikipedia is a very unusual community in many respects. Do other online communities follow Wikipedia’s pattern of rise and decline? Does increased use of quality control systems coincide with community decline elsewhere?

In a paper I am presenting Thursday morning at the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI), a group of us have replicated and extended the 2013 paper’s analysis in 769 other large wikis. We find that the dynamics observed in Wikipedia are a strikingly good description of the average Wikia wiki. They appear to reoccur again and again in many communities.

The original “Rise and Decline” paper (I’ll abbreviate it “RAD”) was written by Aaron Halfaker, R. Stuart Geiger, Jonathan T. Morgan, and John Riedl. They analyzed data from English Wikipedia and found that Wikipedia’s transition from rise to decline was accompanied by increasing rates of newcomer rejection as well as the growth of bots and algorithmic quality control tools. They also showed that newcomers whose contributions were rejected were less likely to continue editing and that community policies and norms became more difficult to change over time, especially for newer editors.

Our paper, just published in the CHI 2018 proceedings, replicates most of RAD’s analysis on a dataset of 769 of the largest wikis from Wikia that were active between 2002 to 2010. We find that RAD’s findings generalize to this large and diverse sample of communities.

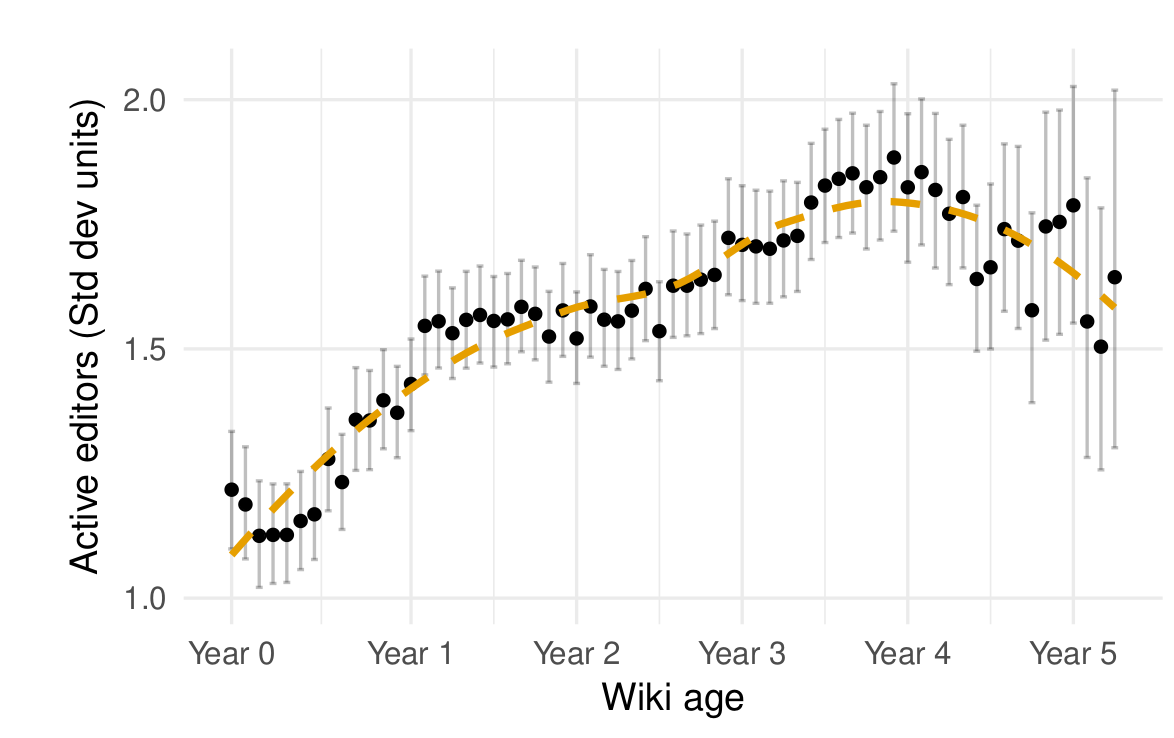

I can walk you through some of the key findings. First, the growth trajectory of the average wiki in our sample is similar to that of English Wikipedia. As shown in the figure below, an initial period of growth stabilizes and leads to decline several years later.

We also found that newcomers on Wikia wikis were reverted more and continued editing less. As on Wikipedia, the two processes were related. Similar to RAD, we also found that newer editors were more likely to have their contributions to the “project namespace” (where policy pages are located) undone as wikis got older. Indeed, the specific estimates from our statistical models are very similar to RAD’s for most of these findings!

There were some parts of the RAD analysis that we couldn’t reproduce in our context. For example, there are not enough bots or algorithmic editing tools in Wikia to support statistical claims about their effects on newcomers.

At the same time, we were able to do some things that the RAD authors could not. Most importantly, our findings discount some Wikipedia-specific explanations for a rise and decline. For example, English Wikipedia’s decline coincided with the rise of Facebook, smartphones, and other social media platforms. In theory, any of these factors could have caused the decline. Because the wikis in our sample experienced rises and declines at similar points in their life-cycle but at different points in time, the rise and decline findings we report seem unlikely to be caused by underlying temporal trends.

The big communities we study seem to have consistent “life cycles” where stabilization and/or decay follows an initial period of growth. The fact that the same kinds of patterns happen on English Wikipedia and other online groups implies a more general set of social dynamics at work that we do not think existing research (including ours) explains in a satisfying way. What drives the rise and decline of communities more generally? Our findings make it clear that this is a big, important question that deserves more attention.

We hope you’ll read the paper and get in touch by commenting on this post or emailing me if you’d like to learn or talk more. The paper is available online and has been published under an open access license. If you really want to get into the weeds of the analysis, we will soon publish all the data and code necessary to reproduce our work in a repository on the Harvard Dataverse.

I will be presenting the project this week at CHI in Montréal on Thursday April 26 at 9am in room 517D. For those of you not familiar with CHI, it is the top venue for Human-Computer Interaction. All CHI submissions go through double-blind peer review and the papers that make it into the proceedings are considered published (same as journal articles in most other scientific fields). Please feel free to cite our paper and send it around to your friends!

This blog post, and the open access paper that it describes, is a collaborative project with Aaron Shaw, and Benjamin Mako Hill. Financial support came from the US National Science Foundation (grants IIS-1617129, IIS-1617468, and GRFP-2016220885 ), Northwestern University, the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University, and the University of Washington. This project was completed using the Hyak high performance computing cluster at the University of Washington.

Discover more from Community Data Science Collective

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One Reply to “Revisiting the ‘Rise and Decline’”