We all wear a lot of hats as researchers. Cowboy hats as we lasso and wrangle data. Noir-style fedoras when we are pinning post-it’s to a wall and stringing together our evidence. Berets when we ponder over the perfect artistic metaphor to describe our results. Sitting dusty in the corner is the tocque, the baker’s cap. We don the tocque, the billowing white like a cloth mushroom, when we’re kneading our ideas and getting ready to bake them. Too often, we don’t really linger in that role, our ideas need to move forward: there are deadlines to meet and papers to publish! However, once a year, the CDSC invites its members to become bakers and play around with our half-baked ideas together in the Great Half Bake-Off.

One of the hallmark’s of the CDSC’s annual retreat, in which our distributed collective gathers at one of the member universities to be merry (and work) together in meat space for a few days, is the annual Great Half Bake-Off (GHBO). The Great Half Bake-Off is an opportunity for members of the group to present an idea in a rapid-fire way that they’re interested in. They might not know where to start with the idea, or the idea seems too big or out there to seem feasible.

The half-bake off, being a part of our retreat at the beginning of the academic year does a lot to glue the group together. With an intention of sharing an idea that we actually care about, but might in other instances be too afraid to share because it feels too undercooked, we become comfortable sharing our ideas with each other, no matter what the stage of thought we’ve put into the project idea.

The exercise helps us learn about each other as it reveals the gulf between what we all work on and what some of the projects we only dream about are. It helps us become more comfortable with airing out our inspirations and ideals. It overall encourages a moment of playfulness and camaraderie.

How Do We Bake (Or, How You Can Host Your Own Great Half Bake-Off)

The logistics for the GHBO are relatively simple. Notify your bakers at least a few weeks before your event to think about what half-baked ideas they want to bring to the table. Provide a collaborative slide deck for them to include a slide if they’d like to organize their half-baked thoughts in that way. We give our bakers 2-3 minutes (but no more!) to present their ideas, and a minute or two to field questions. Then, at the end, for the grand prize of a Silly Little Trophy, we all vote for who had the most half-baked idea. This is a key element to the process: voting on the merits not of the idea’s potential success or creativity, but the vague, unreliable measure of “half-bakedness.”

This is the slide template we give in advance, should people want to use it! Sometimes it’s nice to bake with a recipe. :’)

Some Half-Baked Categories to Prepare Your Bakers:

- Long Shots – Maybe there’s a project within your repertoire, but you’re not sure how you would find the time, money, or energy to see it through. Sound’s half-baked!

- Mysteries – Have a research question that you’re just not sure where even to begin to answer? Perfect!

- New Flavors – Perhaps you have a project that you’re thinking about but it uses a method that you’ve never used (or even seen someone else use!)

- Something Silly – We all have burning questions that might … not add a lot to the public good if we were to answer them. Now’s your chance to talk about those!

- Literally anything else – by now, hopefully you get the idea. As long as it is mushy and half-baked – with enough room for your colleagues to poke at its spongy undoneness, it’s worthy of being called half-baked.

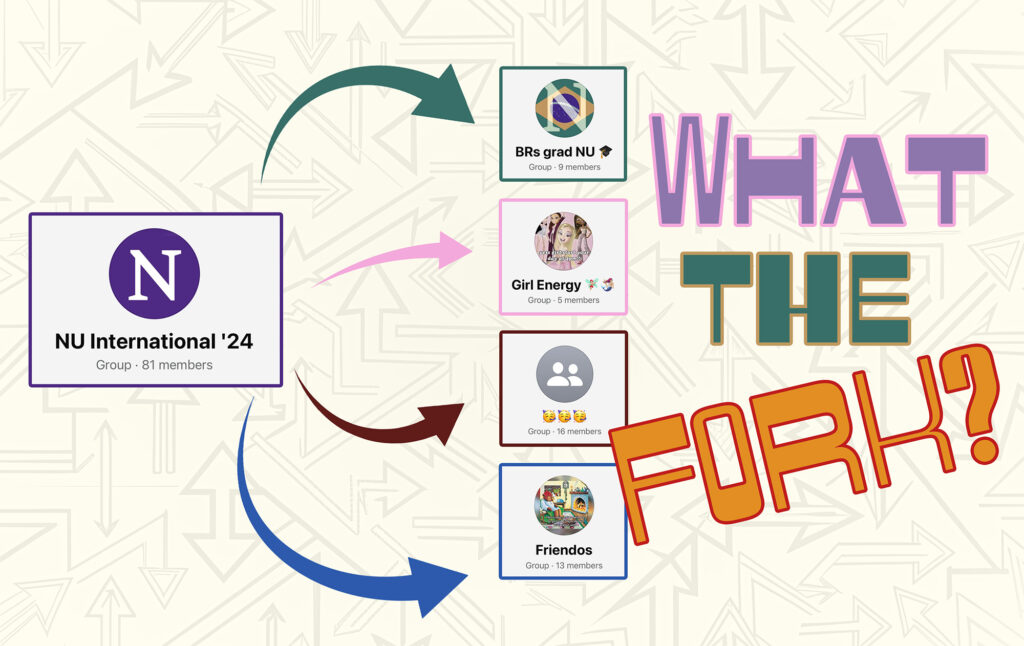

Winner of GHBO 2024, Emily Zou’s, half-baked idea!

What Comes Out of the Half-Baked Off

As we’ve discussed, the main benefits of the Great Half Bake-Off come not necessarily from the immaculate pastries that we pull out of the oven at the end of the ordeal, the goodness of the half bake off exists in the way we get to have a good time with each other, and see deeper into how we each begin to craft our doughs. In fact, more often than not, our ideas from the event many moons later remain just as half-baked as when we presented them. Sohyeon, the 2022 GHBO champion, in a 2024 update on the status of her winning project proposal gleefully remarked that “the idea remains half-baked.”